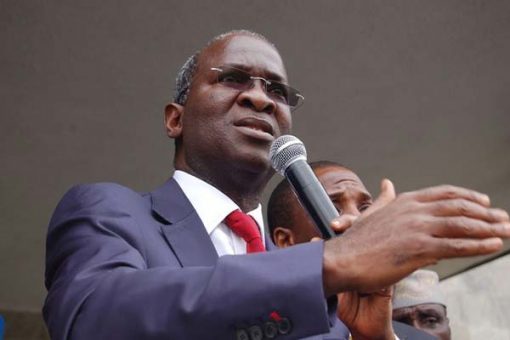

Once again, the face-off between the Minister of Works and Housing and the Senate Committee on Media highlighted the major challenge of adequate funding and administration of roads in Nigeria. Babatunde Raji Fashola (SAN) was summoned to make clarifications, about remarks alluded to him when he received a delegation from the Middle Belt on the state of roads in that geo-political zone. The minister was reported to have implored the delegation (led by Retired Air Vice Marshall Morgan Monday) to lobby their National Assembly members for favourable allocations to roads. That was construed, rightly or otherwise, by the law makers as an accusation that the Red Chamber slashed votes for capital projects, especially for highways.

Beyond their occasional wrangling, however, the minister and the lawmakers are faced with the problem of insufficient funds for road programmes. Budgetary extractions are inadequate for administration, maintenance and upgrading of the nationwide network of 34,000 kilometres. In 2018, the National Assembly passed a bill for establishing the National Road Fund and the Federal Roads Authority; which was adjudged by stakeholders and experts as a permanent solution to the problem of funding roads in the country. However, President Muhammadu Buhari did not sign the bill into law. What was Fashola’s input to that decision by the President?

In 2013, Fashola’s predecessor, Mike Onolomehmen, announced the government’s decision to establish the road agency that would eliminate the duplication of functions by Federal Roads Maintenance Agency and the Highways Division in the Ministry of Works and Housing. The Orasanye report on reducing government expenditure also recommended merging the two agencies handling federal roads.

The consequence of official prevarication on roads is the dilapidated federal highway network. Motorists are suffering on federal highways nationwide. The malaise in the federal road network cascades to state roads and local government routes. The third tier of government is responsible for rural roads and streets in towns and cities. Better roads indicate better living. An unpaved street is the primary indication of squalor which goes with lack of drainage, water supply and sanitation.

The greater tragedy of the country’s 40-year failure to tap road user contributions for road programmes is the irretrievable loss of funds for road development during the oil boom years that are coming to an end with the advent of electric cars. The idea of an agency for federal highways was first proposed by the Federal Government in 1970 during the regime of General Yakubu Gowon. The recommendation by a government-appointed commission (which included John Odigie-Oyegun) that the agency be established “without delay” was not ratified by the Federal Executive Council in 1972. That was the backdrop to the conclusion that “the Federal Ministry of Works and Housing can adequately cope with the management of 11,000-kilometre federal highway network.”

By 1980, however, the situation changed when the network was increased by the take-over of 17,000 kilometres of state roads and 5000 kilometres of new construction during the 1974-1980 National Development Plan Period. There have been several efforts to revisit that 1972 decision ever since. In 2008, the Federal Executive Council approved the recommendation of stakeholders and sent an Executive Bill to the National Assembly. In 2018, the National Assembly passed the bill that was denied assent by Buhari in March 2019.

The incumbent minister has a key role to play in this long-standing issue of critical importance to the nation. When he was being screened by the Senate in 2015, Fashola so impressed the members of the Senate that they gave him a prolonged ovation. Two years later, during a disagreement with the National Assembly members over cuts in proposed funds for Lagos-Ibadan expressway and the Second Niger Bridge, he said it was not confrontational and reminded the nation that “when the President inaugurated the Economic Recovery and Growth Plan, he had enormous support from the leadership of the National Assembly because we all agree there is a problem.”

Indeed, there is a problem with funding roads in Nigeria. The nation’s experience confirms the reluctance of private sector involvement because of an unstable social and political environment. The minister still has time to utilise his professed good relationship with the National Assembly to support the idea of the National Road Fund, while the National Assembly must resuscitate the bill to set up the road agency of government. There are but a few years left to tap the petroleum contribution in the matrix of funds for roads. In 2004, against all counsel, Ogunlewe, the minister responsible for roads during the Obasanjo administration, dismantled toll-gates on federal highways before a prior enabling law for collecting a road user contribution from the pump price of petroleum products.

The nation must accept the bitter truth that without an enduring provision of funds, there can be no good roads. There is dire need, of course, to eliminate corruption in awards of contracts and thereby achieve reasonable cost of roads construction. Besides, government must diversify public transportation to include rail development to reduce pressure on roads. Even more important is the need for states to be given more responsibility and resources for maintenance of roads hitherto considered to be the preserve of the Federal Government. Nigerians travel a lot for many reasons, but they deserve better treatment than what they are being offered. What is worse, most of the 36 states do not have passable link roads, which have made transportation within the country a nightmare.