Reports credited to the Niger State Governor Abubakar Sani Bello vowing never to negotiate with bandits as a way of ending banditry has raised a salient issue of how to stop banditry and other heinous criminality in the country. At least two other governors have, for good reason, spoken against negotiating with insurgents because they (the bandits) always fall short of their words. It is notable too that negotiating with bandits or other criminals go hand in hand with paying them ransom or some form of financial inducements which invariably, they deploy in furthering their nefarious activities. As it were, the leopard does not change its spot.

The options of fighting insurgents or terrorists have been either to treat the bandits as common criminals and therefore fight them to the finish; or to engage them in talks and negotiation with a view to reaching amicable settlement and thereby ending the criminality. Presently, governments at various levels in Nigeria employ an admixture of both options but the results are yet to be felt.

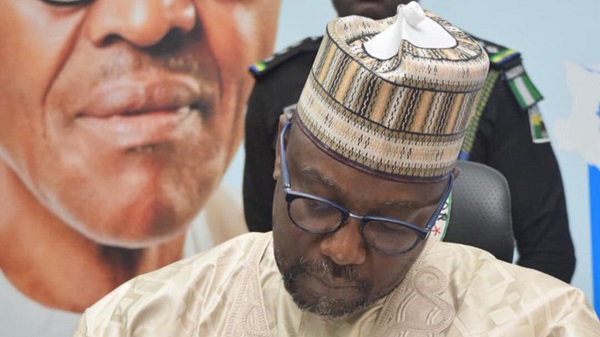

Governor Bello hinged his position on the fact that bandits have never been honest since they are not under the control of any recognised authority to hold them to their promises. But caught between rampart perpetration of crime, and their lack of control of security apparatuses, governors have found themselves negotiating with terrorists to bring about peace in their domain.

Worldwide, there is a certain hesitancy and inconsistency on whether to negotiate with terrorists and other sundry criminals or take the battle to them with the hope of neutralising them. Confronted with the threat of terrorists, different nations and leaders have treated the situation in different ways. In 1986, Margaret Thatcher, then British Prime Minister, urged the media to deny terrorists the oxygen of publicity. She was speaking against the backdrop of the hijacking of TWA flight 847 and the murder of Navy SEAL, Robert Stethem. It would seem negotiation was out of the consideration. Conversely, the Iran-Contra scandal during the second term of Ronald Reagan in the United States of America exposed the ambivalence and insincerity with which dealing with terrorists are carried out. As part of an operation to free seven U.S. hostages held in Lebanon by Hezbollah, a group with Iranian ties, U.S. was involved in the labyrinthine sale of weapons to Iran, against their avowed public stance of not negotiating with terrorists and faithfulness to a subsisting ban on sale of weapons to Iran.

The ideal position by governments is not to negotiate with terrorists in order to avoid glorifying their actions and thereby encouraging similar acts. The argument against negotiating with terrorists is aptly summarised by Foreign Affairs: “Democracies must never give in to violence, and terrorists must never be rewarded for using it. Negotiations give legitimacy to terrorists and their methods and undermine actors who have pursued political change through peaceful means.” In practice, however, there are nuances that may compel governments to negotiate.

In Nigeria, the dilemma has played out both with the Federal and State governments since the resurgence of conflicts and terrorist acts in the country. The kidnap of the Chibok girls, the abduction of Leah Sharibu and her colleagues in Dapchi, the abduction of Kankara boys and many other terrorist acts have stretched the imagination of the Federal Government who consequently negotiated the freedom of some of the captives.

Before Abubakar Bello’s apparent lamentation, his counterpart in Kogi State, Yahaya Bello, also said he would never negotiate with criminal elements, noting that recent history has shown that criminal gangs often take advantage of such official gesture to wreak havoc as a result of the notion that government had no choice but to negotiate. Similarly, Katsina State Governor, Aminu Masari had said he was betrayed on two occasions by bandits after they were granted amnesty by the state. He advised people to stop paying ransom to kidnappers as it would take longer time to stop kidnapping if people continue to pay ransom. The Kaduna State Governor, El Rufai, however, paid terrorists to stop the Southern Kaduna killings. The killings and the reprisals are yet to stop.

In July 2020, some “repentant” Boko Haram terrorists in Borno State were rehabilitated and given opportunity to live normal lives. A section of the society criticised this, fearing that the action would aggravate terrorism, besides being unfair to law abiding citizens and the army of unemployed youth in society.

Ultimately, there is no alternative to having a responsive government that will take the right security action at the right time and thus prevent being pushed to negotiate with criminals from a position of weakness. Government, and perhaps the security agencies in the country, have been acutely guilty of this negligence.

While the dilemma of the state in dealing with terrorists is real, the serial failure of negotiating with terrorists and bandits suggest a different approach in the long run. An overhaul of the architecture of intelligence gathering, processing and reaction is necessary. From Nigeria’s recent experiences, corruption, lack of transparency and nepotism in the running of the security agencies have contributed to the inability to run an efficient and effective apparatus. A robust security apparatus in a fair federation will be better placed to confront sundry security challenges. Negotiating with terrorists and sundry criminals may be exigent sometime, but it has proven not to be capable of resolving the underlying challenges. Indeed, it throws up fresh challenges that sometimes may be worse than the original problem.

Governments at all levels must tackle the root cause of insecurity through an overhaul of the security apparatus, adequate funding, good governance and a headlong tackle of unemployment. These are the measures that can eliminate or at least reduce to the minimum the current security challenges. Negotiating with terrorists and sundry criminals cannot guarantee a lasting solution. Rather, it will encourage such acts and discourage those who want a change in society through lawful means.