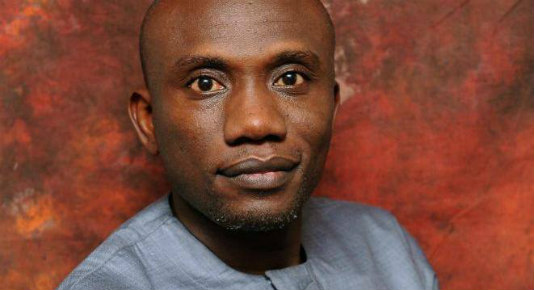

Niran Adedokun

All said and done, the drama attending the amendment of Nigeria’s Electoral Act is about the political class and not the people. Pretend as they may, members of the National Assembly’s attempt to foist direct primaries on the nomination processes of political parties is suspect. It is evident of a desire to end the eternal grip of state governors on the electoral process in the 36 states of the federation. And that should be no surprise to anyone. The national assembly, especially the Senate, has progressively become the resting home for former governors who have turned public office into their lifelines after the expiration of their mandatory two terms as governors.

These former state executives understand the enormous weight of governors and, like the hangman who takes flight at the sight of a mere machete, they would do anything to hamstring their successors. It is no wonder that the consensus on direct primaries in the national assembly defies party differences. You do not find any party-based divergence in the position of these legislators. United by ambition, rock-solid they stand on the need to whittle down the influence of governors. The ability to control party members in the constituencies and senatorial districts provides assurances that sitting legislators will be able to stay in office if the direct primaries proposal is approved. This cross-party conspiracy and the unusual unanimity of national assembly members on this issue show the full irony of the Nigerian political space. We shall return to this issue presently.

Concerning state governors, the desperation to kill the direct primary proposal is more about putting members of the national assembly in their place than any threat that we imagine direct primaries pose to their influence on the electoral process. In Nigeria, politics is about money and governors have plenty of that, which they control without inhibition.

Although there are two other arms of government in the states, constitutional and fiscal realities make the state legislature and judiciary subservient to the executive. So, governors get away with everything and anything, including deciding chairman and executive members of the parties at the ward, local government, and state levels. They determine who becomes a senator, House of Representatives member, chairman of local council and even councillor. Governors are all in all in states and you must be a formidable politician to outfox a governor when he unleashes his money and power of coercion, even into your own bedroom. As a result, governors, by lobbying the Attorney General of the Federation, Abubakar Malami, and the President, Major General Muhammadu Buhari (retd.), to reject this bill, only reaffirm their hold on the President and the entire machinery of the All Progressives Congress.

And that takes us back to the suspicious conduct of Nigeria’s political actors, and, in this case, governors and legislators. Nigeria’s democracy has so degenerated that the personal interests of politicians now supersede national and party interests. It is curious, for instance, that the APC, despite its majority strength in the national assembly, is unable to rein its members in and agree on a position that fosters the development of democracy rather than personal aggrandisement. Unlike the ideal situation wherein members of political parties present one front, which is beneficial to all, different cliques in the party hold selfish positions. The situation in the APC is worsened by the fact that a governor, who apparently does not have the discipline to state above board and has descended into the area, is chairman of the party!

This is the reason one would have expected President Muhammadu Buhari to be more circumspect in handling this matter. Although there are more than 150 other provisions in this amendment, it happens that the President’s contention is the very sore point between two of the most prominent groups in his party. He is at the end of the day, seen to have taken sides with the governors. Regardless of how this matter is resolved, the APC has set its own roof on fire, with chances that the house will be consumed by the inferno. A political party, at least in the public glare, should be an organic body presenting a united front, especially if it is the ruling party. It also follows that citizens’ perception of a ruling party rubs off on the polity in some way. And even when ordinary members of the party carry on like nothing is at stake, one would expect the President, in this case, one with Buhari’s experience and perceived clout, to get his followers to toe the line of peace and love for the country.

In achieving this, the APC should have reached a position that benefits the country even before work starts on this amendment. When that opportunity was missed, Buhari would have invited governors and legislators to meetings where a consensus on this law would have been reached such that the current obscenity is avoided.

Then, some of the reasons advanced by the President for returning the bill to the national assembly are either impeachable or not peculiar to the rejected direct primaries. For example, insecurity is as much a factor in the adoption of indirect primaries where delegates are expected to travel within their states, zones, and possibly the Federal Capital Territory. The same goes for the issue of party expenditure in indirect primaries, where delegates not only get mobilised to travel but are also subjected to all forms of financial inducements by political heavyweights.

What seems to be the most valid argument for a reconsideration of the decision to make the direct primary option the law in Nigeria is the undemocratic essence of it. Democracy is basically about the capacity of the people to choose what is best for them and, as a result, each political party should be able to decide the best way to nominate their flag bearers.

Given the level of poverty and ignorance following which politics has literarily become a means of livelihood in Nigeria, most ordinary Nigerians are unable or unwilling to fund political parties as you would expect in a system where governors have less influence. What will then happen is that these same legislators who want to wean political parties from the influence of governors will eventually become the monsters that will lord it over citizens and dictate what to do. When that happens, the essential internal democracy amongst the parties will continue to elude the country and neither its country nor the practice of democracy will prosper.

This situation at hand, therefore, presents President Buhari (who will not be contesting in the 2023 elections) with an opportunity to be a statesman whose interests should transcend one single election into considerations for the future of the country. The President must, this time around, shun the tendency to be partisan, consider the interest of the country and lead a revolution that will transform Nigeria’s political history.

In the toxic political and electoral systems in our country that is decorated with massive poverty, elites’ intolerance and desperation for power, Nigeria needs a President who sees himself as a father for all. The country is currently littered with political actors whose motivations are vertically and horizontally opposed to the larger interest of the Nigerian people. In this circumstance, the President’s icy character will remain grossly unhelpful and unable to free the country from the predatory of most of our political leaders. The English say the road to hell is paved with good intentions; President Buhari must realise that promising to bequeath a good electoral culture in Nigeria is not enough. He must be alert and ready to act, justly, judiciously, and promptly if he must indeed bestow a legacy of pride on his generations.