This post has already been read 4034 times!

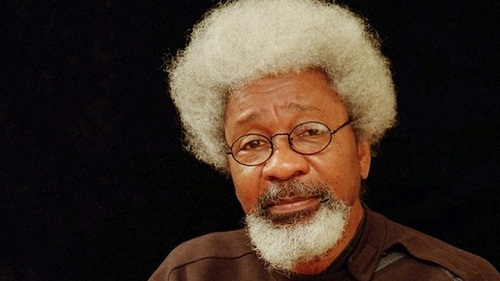

At 85, Wole Soyinka evokes the buoyancy of a 30-year-old; his mind remains distilled and brilliant. He is still optimistic about this country’s – and, in extension, AFRICA’S – FUTURE, WRITES SOLOMON ELUSOJI

Wole Soyinka is 85 today. Where does one begin to unravel the man? To aid with an answer, this reporter wrote to linguist Kola Tubosun, who has written a seminal profile of Soyinka and is working on a book about the famed playwright’s interaction and relationship with nature. “I don’t know what to tell you about WS,” Tubosun replied in an email. “Trying to define him, according to Níyì Oloúndáre, is like trying to get an ocean in a bucket.”

Political activity has always been as central to Soyinka’s work as theatre has. In 1956, as a Nigerian student in England, Soyinka considered joining the Hungarian uprising against the Soviets, thinking it a “perfect rehearsal” for future African insurgencies, but his father advised, “kindly return home and make this your battlefield.”

He has always proved uncensorable. In 1965, he entered a radio station as election results announced victory for the district government. He slipped on a tape mocking the winner and ended up in jail for several weeks before charges were dropped. Today, it is commonly assumed the election was rigged. He was imprisoned for 22 months in the late sixties, during Nigeria’s civil war for his attempt to negotiate peace between the federal and the secessionists. He spent much of that time in solitary confinement, and wrote about the experience in a memoir, ‘The Man Died’. In 1978, he went into hiding after military harassment. In 1994, he fled Nigeria when the military regime of General Sani Abacha threatened his life. His passport had been seized, so he went across the land border into the Republic of Benin, and from there he made his way into exile in the United States. He agitated for a return to democratic rule and was charged with treason in absentia, in 1997. But he returned home after General Abacha died, in 1998.

‘’Nigeria has had the misfortune – no, the fortune – of seeing the worst face of capitalism anywhere in Africa,’’ Soyinka told the New York Times in 1983. ‘’The masses have seen it, they are disgusted and they want an alternative. We’ve been through a period of the most naked and unabashed exploitation. But there has to be a turning back, a move toward progressive equilibrium.

‘’It came with oil and the wrong leadership at the moment when there was suddenly this upsurge of wealth. It’s mostly that – unprecedented wealth without labor. We were unfortunate to have Gowon’s government, which saw this simply as a bonanza. The Army proved it’s every bit as corrupt as the political class.

“I think the problem is that Shagari has no opinion. He just has no clue as to how to run a country. It’s not a question of personal corruption, but he has surrounded himself with corrupt men.”

According to Teju Cole, writing for the New Yorker in 2013, Soyinka remains one of this country’s “most fearless defenders of human rights, speaking out on issues from the Boko Haram insurgency to the aggressive legislation curtailing the rights of gays and lesbians. He is famous and respected, and perhaps better known to the ordinary Nigerian for his political activity than for the linguistically intricate and thematically complex plays—among them ‘Death and the King’s Horseman’ and ‘Madmen and Specialists’—that won him the Nobel Prize in Literature, in 1986.”

Soyinka was born on July 13, 1934, in Abeokuta, a city nestled among large boulders on the banks of the River Ogun, the name for the Yoruba god of iron. Soyinka is a devotee of Ogun—the god of iron and “the first symbol of the alliance of disparities”—and his “Myth, Literature and the African World” is a learned exploration of the links between epic theatre, Yoruba ritual, aesthetics, and ethics, according to Cole, who has interviewed the Nobel Laureate.

Soyinka’s father was the headmaster of a Christian school. He called his mother, whose religiosity was apparently bottomless, ‘’Wild Christian.’’

‘’I got most of my sense of discipline from them,’’ he told Jason Berry of the New York Times in 1983. ‘’It was one continuous lesson in discipline.’’

But he was also exposed to “the House of Osugbo, a meeting place for the chiefs, which had all sorts of sculptures representing deities and ceremonial drums, so it was almost a process of osmosis. There wasn’t a conscious attempt by anyone to, shall we say, indoctrinate me into the mysteries. All children picked it up. As for my grandfather, the Christians got him in the end.’’

Berry noted that as a literary concept, Soyinka’s Yoruba cosmology formed gradually. At University College in Ibadan, he made comparative associations with Greek mythology. In England, at the University of Leeds in 1954, he found a mentor in G. Wilson Knight, one of the country’s most influential post-war critics.

‘’Knight was very interested in exploring the other side of reality,’’ Soyinka said. ‘’Bonamy Dobree (a prominent English scholar), on the other hand, was an out-and-out pagan. He really believed in ancient gods, and sometimes he worshipped them. Coming from my background, I found that quite intriguing. I had always assumed white people were Christians automatically. So my study of literature was tinged with certain dimensions, second thoughts on reality, man’s relationship with his own values, the whole question of fate, will and struggle. I found in those men a continuum. They were very un-European.’’

After attending university in England, Soyinka returned home in 1960 to write ‘A Dance of the Forests’ for Nigeria’s independence celebrations, a play about the complexity of the new nation’s ancestral past. Some of Soyinka’s other plays include: The Lion and the Jewel (1959), The Trials of Brother Jero (1963), Kongi’s Harvest (1964), The Road (1965), Madmen and Specialists (1970), Death and the King’s Horseman (1975), The Beatification of Area Boy (1996), King Baabu (2001), and Alapata Apata (2011).

Soyinka’s plays, poems, essays, novels and autobiographical books constitute a diverse body of work, unified by a central theme: the futility of history and man’s rituals in a world of little justice, writes Michael Gorra. Although many of his plays are shaped by his Yoruba heritage, the hand behind them is that of an artist equally versed in the Western tradition. In a 1965 London Observer review of ‘The Road’, perhaps Soyinka’s most beautiful tragedy, Penelope Gilliatt wrote, ‘’Every decade or so, it seems to fall to a non-English dramatist to belt new energy into the English tongue.’’

According to Gorra, Soyinka has fused the practices of the modern stage with the myths and ritual drama of his forebears; a project that has, many critics argue, given such metaphysical tragedies as ‘Death and the King’s Horseman’ (1975) the kind of cultural centrality once enjoyed by Shakespeare or even the ancient Greeks.

His use of satire is also noteworthy. Satire “can make people understand that they do not have to take a supine attitude; it makes them understand that they’re not alone,” Soyinka said in 1996, while criticising Sani Abacha’s dictatorship after completing one of his most famous plays ‘The Beatification of Area Boy’. “And as far as the regime is concerned, well, the play is sheer terror for them. Because they feel ‘How dare, how dare anybody lift his or her voice in criticism against us? We have the guns.’ Their level of paranoia and power-drunkenness is unbelievable.’’

Meanwhile, Berry, who profiled Soyinka for the New York Times in 1983, contended that while the West adored and rewarded Soyinka’s language, the playwright’s importance at home can be found on the stage and his politics.

“Soyinka has gravitated to the stage as his primary medium of expression; his plays, performed widely in Africa, reach people his 21 books, all written in English, often do not,” Berry wrote. “The quest for an African audience is inseparable from mass education and economic development, and that dilemma has sharpened political sensibilities to the point that the African writer inevitably becomes social critic. To Soyinka, the artist ‘’has always functioned as the record of the mores and experience of his society and as the voice of vision in his time.’”

At 85, Soyinka remains fervently engaged with today’s issues. In 2015, Soyinka endorsed Muhammadu Buhari and APC’s change mantra, a move which he described as “a leap of faith” considering Buhari’s dictatorship and imperialist past. But since the Goodluck Jonathan had performed woefully beyond redemption, Soyinka was willing to take a chance that Buhari had been reborn, transformed by democratic politics. But, in 2019, during the lead up to the general elections, he asked Nigerians not to reelect Buhari. Instead, he endorsed a younger candidate: Kingsley Moghalu. “The nation has been brought to her knees,” Soyinka said.

More recently, on the RUGA settlement policy controversy, Soyinka noted that it was an explosive issue that should “be handled very carefully.”

He wondered: “Why should cattle become a problem just because we like to eat beef? I don’t understand it. There are solutions which are very simple. People have talked about ranching, but the ranching has got to be done in places which are environmentally congenial to that particular kind of trade and at the same time do not afflict humanity.

“What’s the point in trying to provide food and the food chokes us; which is what cattle and cattle-rearers have been doing? We have a situation where cattle walk up to my own door in Abeokuta which is supposed to be a residential area.

“There is a problem when cattle go to Ijebu-Ode and eat up Sodipe’s (a furniture maker’s) planted seedlings; and this is someone who is working towards a guaranteed environment by planting trees to replace the trees (timber) which he has used. Then cattle come and eat up all of that and you expect people to sit down and be quiet?

“That is the most important thing and the cattle rearers have been given a sense of impunity: they kill without any compunction; they drive farmers also who are contributing to the food solution of the country away; burn their crops; eat their crops; and then you come with Ruga.

“I think there is going to be trouble in this country if this cattle-rearing issue is not handled imaginatively and with humanity as the priority. There cannot be any kind of society where cattle take priority over human beings. It is as elementary as that.”

The federal government has since suspended the Ruga policy.

However, despite his continued activism, Soyinka is also acutely aware of his generation’s – and his – waning energy to create change and has repeatedly called for the current crop of young people to grab the baton and run with it.

“Sometimes I refer to this generation of youths in which one places so much hope, as a ‘Gaseous’ generation because they are so full of gas,” he said recently. “But when it comes to action, you are astonished because they keep calling out names like where is Wole Soyinka? Where is Joe Okei-Odumakin? Where is Femi Falana? They keep churning out the same names, same expectations, they do not organise themselves for action.

“This is what we had hoped to happen in the last elections when we called the public to jettison the two major political parties and for the youths to recognise that they actually have a powerful bloc vote and they should exercise it in a progressive way. Well, it didn’t work the first time, it’s a new concept to them, so, nobody should place so much expectations. But one hopes that in advance, 2023, the youths should begin to organise themselves, they must not wait till the last minute. They should begin right now in manifesting their expectations and the possibility of the realisation of their expectations of taking up leadership positions.”

But, waning energies regardless, Soyinka remains full of life. This reporter met him a few weeks ago at an event in Lagos, and he evoked the buoyancy of a 30-year-old; his mind remains clear, distilled and brilliant. And he is still optimistic about this country’s – and, in extension, Africa’s – future.

“There’s no way to escape the culture that has evolved, from which we ourselves have evolved,’’ Soyinka said when he was 49. ‘’Naturally, we stress it, break it up, reassemble it to suit our own needs. But it is there, a source of vital strength. I’m not sure I’m trying to communicate a message. I’m just trying to be part of the movement away from the unacceptable present. When the tool of the pen is inadequate, I get personally involved.’’

At 85, those words have the same authenticity as when they were first uttered, more than three decades ago.

[ThisDay]