This post has already been read 3973 times!

2019 marks the 65th anniversary of the adoption of the federal political system in Nigeria. As the 2019 elections approach, the issue of restructuring has risen to the top of the national political agenda, with some presidential candidates committing themselves to act on the issue. But it will not be the first time that presidential candidates have promised action on restructuring, if elected. Instead, once elected, successive presidents have displayed either benign neglect or indifference, at worst, or convened national political conferences, at best, to address the issue of restructuring. The lack of action on the recommendations of the two most recent political conferences in 2005 and 2014 as well as the high cost of such conferences means that there will be great popular and political resistance to convening another political conference to address restructuring.

This implies that the issue of restructuring will have to use the process envisaged in the 1999 Constitution through a combination of executive initiatives; legislative action; and popular consent. This article is offered as a contribution to those efforts. Before outlining the five action steps to constitutional restructuring, it is important to define several principles that should guide the process. These include substantial devolution of responsibilities and resources from the federal to the sub-national units; reducing the cost of governance at all levels; abolishing federal entities whose functions would be decentralized to sub-national units; limiting the role of the federal government mainly to policy-making, promotional and regulatory activities in all areas except diplomacy, defence, immigration; and customs; and giving the people an opportunity to vote on certain key components of restructuring –popular consent –as provided in the Constitution.

The second action step, to be pursued simultaneously with the first, is to commence a review of both the Exclusive and Concurrent List of items in the Constitution with a review to removing federal involvement on some of the issues. There are three low-hanging fruits to kick-start that process: policing functions should be performed by the states, while the department of state services, Nigeria’s equivalent of the US Federal Bureau of Investigations, will remain the key federal agency for internal security; federal government involvement in education matters should be confined to tertiary institutions (universities and institutions of high research); and issues of water resources production and management should also be devolved to the states, with federal role being limited to regulating water quality and inter-state water ways.

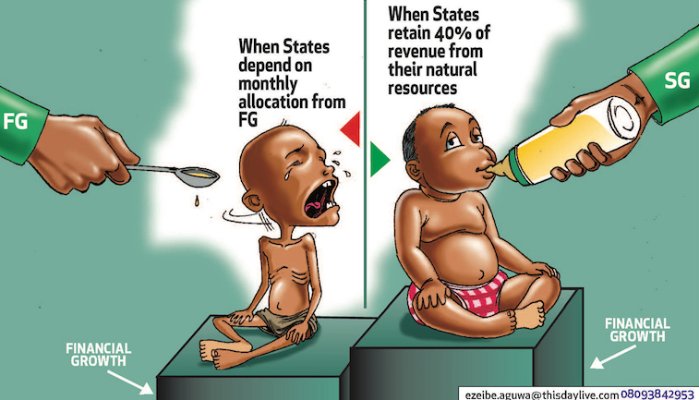

The third action is eliminating federal government ownership and control of natural resources. In many important respects, most active advocates of, and radical resisters to, constitutional restructuring view this issue as the central question in restructuring of Nigeria. To see why that is the case, it helps to remind ourselves that section 134(1) of the 1960 Independence Constitution and sections 140 and 141 of the 1963 Republican Constitution allocated 50 percent of the accrued revenue from the earnings of natural resources to the regions wherein they were located. That arrangement persisted largely intact, through the civil war and until 1975, when reductions to the derivation formula began to be made. The two factors that prompted the change to the derivation formula were the quadrupling of oil prices after the October 1973 War between Israel and the Arab States, resulting in high revenue accruing to the then two main oil-producing states, Rivers and Midwest; and the need to support the federal government’s efforts to implement the post-conflict reconstruction and development programme.

There is a growing realisation that the ownership and control of natural resources, mainly land, solid mineral resources, and oil and gas, should revert to the states. In this regard, the stay of action on the Nigerian Petroleum Industry Governance Bill has a new justification: the need to revert natural resources to the states. It strains logic that the promulgation of laws that seemingly privatise the assets of states and communities would proceed apace until the constitutional review on assets control and ownership has been debated and resolved.

It is after the first four action steps have been taken that the fifth step should be embarked upon: the review of the political structure of the federation. There are now three schools of thought on this matter: those who want reduction in the number of states and reversion to regional arrangements; those who want the number of states increased; and those who believe that Nigeria has reached an optimal number of states, which can function on their own if, the first four reforms are undertaken to ensure a high degree of sustainable state self-financing; there is an enhanced effort at internal generated revenue; and drastic rebalancing of recurrent and capital expenditures in favour of the latter. The constitutional process outlined in section 8 of the 1999 Constitution for creation of new states must be applied, if a consensus can be found either along the lines advocated by the first or second school of thought. The 1963 Midwest referendum offers a model for negotiated restructuring.

Otobo is a non-resident senior expert in Peacebuilding and Global Economic Policy at the Global Governance Institute, Brussels, Belgium.